- Average house price has increased by £57,600 since start of pandemic

- Wales maintains its top position for the tenth month running with the highest property price increase of the 10 GOR areas in England and Wales

- Average house price £373, 471, up 1% on April and 9.8% annually

Richard Sexton, director at e.surv, comments:

“The performance of house prices in England and Wales reminds us of the old maxim that records are made to be broken.

“The average price paid for a home in England and Wales in May 2022 was £373,471, up 1.0% on the average price paid in April. But if we look back to March 2020, we can see that prices are now some £57,600, or 18.2%, above those at the start of the pandemic. It absolutely makes clear what an impact a sudden, pandemic driven, rise in demand has had on a lack of supply issue that has been with us for the last twenty or so years.

“Wales continues to out-perform other regions with the highest annual growth rate, a position it has now held for ten months, but in second place is Greater London, where prices over the twelve months have risen by 11.1%. London’s fortunes are clearly reflected in the story of the pandemic too. During the pandemic’s peak, price growth in London had been the lowest of all the areas as purchasers raced for space further afield. However, from March this year and the onset of hybrid working, we began to see that buyers were moving back into central London and its commuter belts.

“London is also benefitting from a bounce back from returning overseas buyers. This has resulted in an increased level of purchases. Kensington and Chelsea and the City of Westminster have both recently returned to substantial annual growth rates, reaching 16.6% and 32.2% respectively in April.

“The economic headwinds that grab so many headlines are being offset by a systemic lack of supply, full employment, wage increases and, for some at least, the savings that have been amassed over the last two years from changes in working patterns. The growth in single person dwellings too have had an impact on availability of property.”

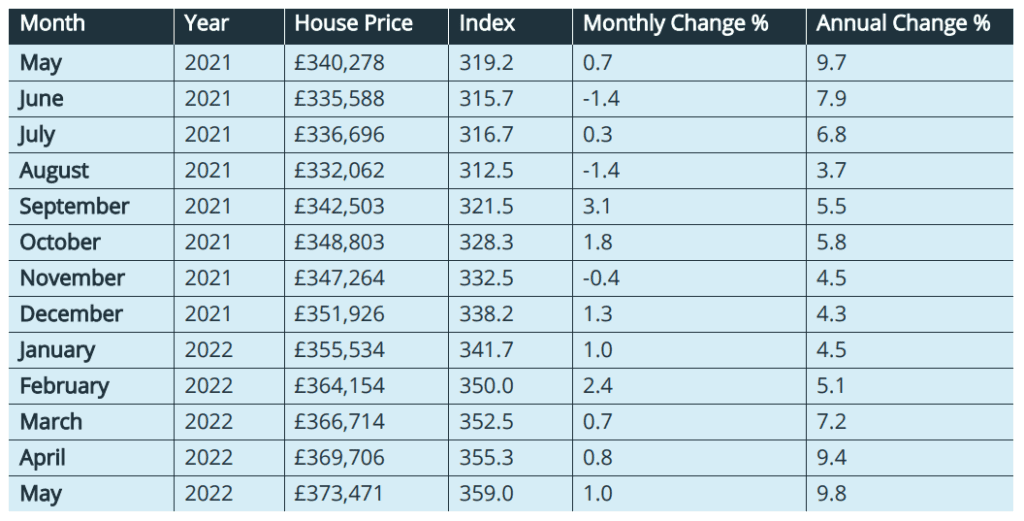

Table 1. Average House Prices in England and Wales for the period May 2021 – May 2022

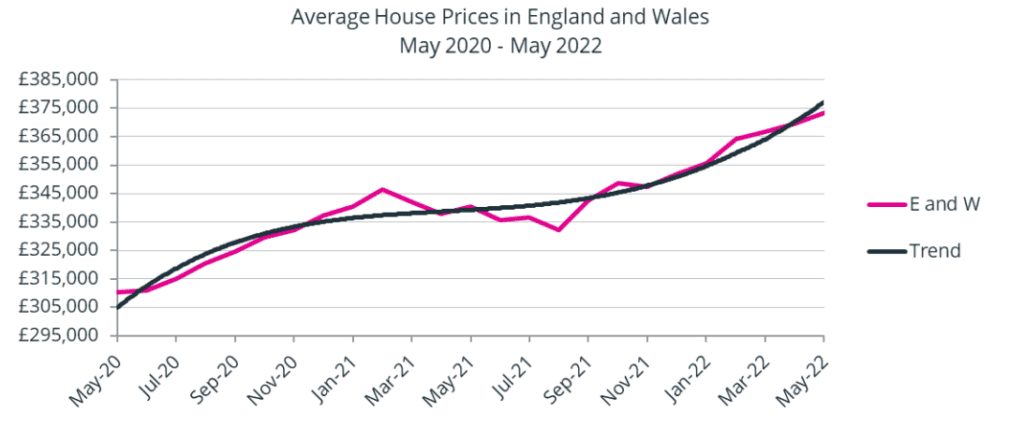

Figure 1. The average house price in England and Wales, smoothed, May 2020 – May 2022

The rise in house prices continues unabated. The average price paid for a home in England and Wales in May 2022 was £373,471, up some £3,750, or 1.0%, on the average price paid in April. This sets yet another new record level for England and Wales – and for the seventh time in the last eight months, thus underlining the recent strength of the market. Prices are now some £57,600, or 18.2%, above March 2020 levels, at the start of the pandemic.

As Figure 1 above shows, the average house price in England and Wales has continued to increase throughout the first five months of 2022 on a near straight-line basis, confounding all the predictions of a slowing growth rate – driven by a variety of factors – but including the increased cost of living pressures on consumers. As shown in this report, house prices throughout England and Wales have continued to climb in 2022, despite that wider context, highlighting the strength of underlying demand.

Average Annual Regional House Prices

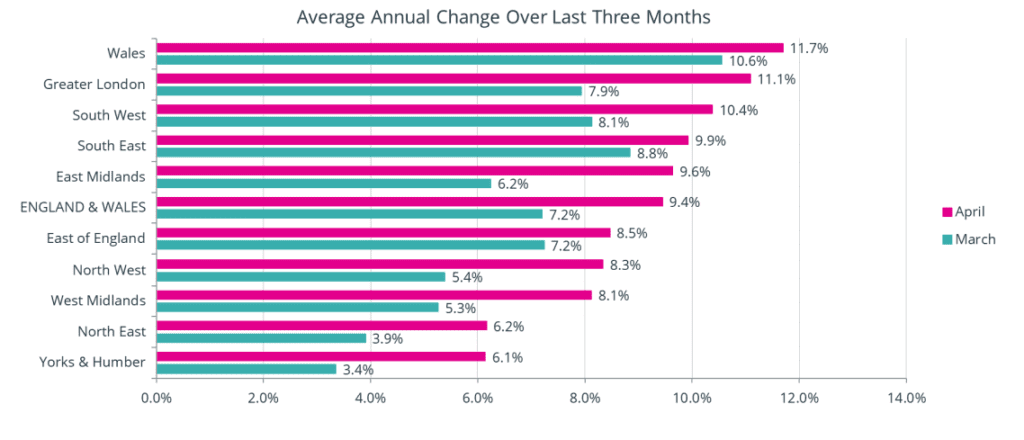

Figure 2. The annual change in the average house price for the three months from March 2022 to May 2022, analysed by GOR

Figure 2 shows the percentage change in annual house prices on a regional basis in England, and for Wales, averaged over the three-month period of March to May 2022, compared to the same three months in 2021. These figures are produced on a rolling three-month basis, with Figure 2 showing the similarly averaged figures from one month earlier.

All ten GOR areas are experiencing rising prices over the last twelve months, with nine of the ten setting new record average house prices in April 2022, the one exception being the East of England, where prices in Essex, the largest component part of the East of England in terms of house sales, fell by 0.3% in the month.

Wales remains the GOR area with the highest annual growth rate, a position it has now held for ten months. Twenty-one of the twenty-two local authority areas in Wales have seen prices increase over the period, the one exception being Denbighshire. Seven local authority areas in Wales have annual house price growth in excess of 15%, the highest being Carmarthenshire, where average prices have increased by 25%, with detached homes in the area rising from £265k in April 2021, to £325k one year later. The rise in detached prices is almost certainly a consequence of the desire for additional space among purchasers arising from the restrictions of the pandemic and the policy of, where possible, ‘working from home’ – the county is frequently referred to as being the “Garden of Wales”.

In second place is Greater London, where prices over the twelve months have risen by 11.1%. As shown in Figure 3 below, price growth in London had been the lowest of all the 10 GOR areas during the pandemic, as purchasers looked to move out of the capital into the more open countryside of the South East and beyond. However, from March 2022 onward, we began to see that buyers were moving back into central London, as offices in the capital started to re-open. Additionally, the quarantine rules that had been in place for visitors to the UK were removed, allowing overseas buyers to travel to the United Kingdom with more confidence. This resulted in an increased level of purchases, with areas such as Kensington and Chelsea and the City of Westminster proving to be favoured locations. These two boroughs have recently returned to substantial annual growth rates, reaching 16.6% and 32.2% respectively in April.

All ten GOR areas have seen an increase in their annual rates of growth, compared to the previous month. The GOR area with the largest increase in its growth rate is the East Midlands, up from 6.2% last month, to 9.6% this month, followed by Greater London, up from 7.9% to 11.1%.

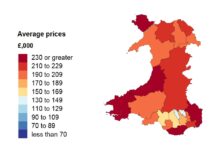

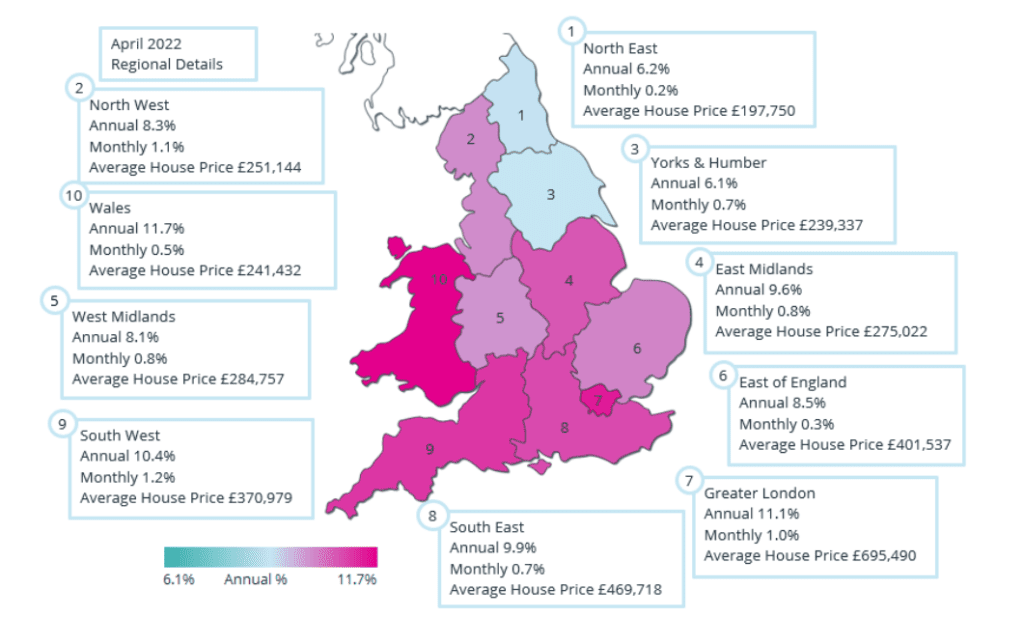

England and Wales Regional Heat Map

These different trends are evident in the Regional Heat Map shown below for April 2022. There are three distinct groupings in England and Wales in terms of house price growth, with both North/South and East/West dimensions. In the South we have the South West, the South East and Greater London, with highest rates between 9.9% and 11.1%, to which we need to add Wales at 11.7% and the East Midlands at 9.6%. We then have the more north western part of England including the North West and the West Midlands at 8.3% and 8.1% respectively, to which we can add the East of England at 8.5%. Finally we have the East coast locations of the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber, with the lowest rates of 6.2% and 6.1% respectively.

The housing market in early summer 2022

Past experience tells us that it takes time for macro-economic changes to impact the housing market. Partly this is because only a small proportion of homes are being traded at any one time, and of course the scale of any impact on households varies enormously. In addition, the mortgage market tends to respond to changed conditions quite slowly, and not least when competitive pressures are intense. The upshot of this is that the long-predicted downturn has yet to materialise, and as reported here, the current market has remained buoyant. We will follow market evolution month-by-month. It is worth noting that the government is due to make further housing announcements, and it seems likely that home ownership will remain a focus. It is thus possible there will be further stimulus measures, but it is hard to predict precisely what they might be, not least given the political and economic backdrop.

April – Annual Price Trends

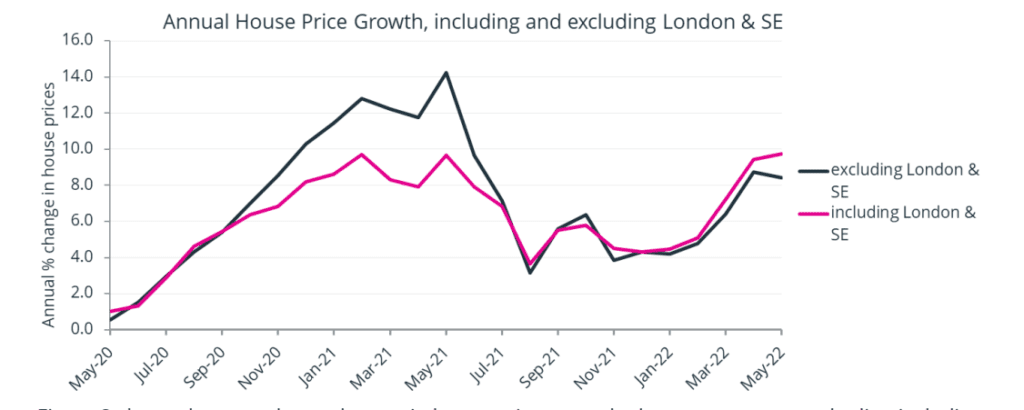

Figure 3. The annual change in house price growth in England and Wales, for the two-year period from May 2020 to May 2022, including and excluding Greater London and the South East.

Figure 3 shows the annual growth rates in house prices over the last two years, one plot line including Greater London and the South East, along with the remainder of England and Wales (the red line), and the other excluding Greater London and the South East (the black line). The impact of trends from September 2020 to July 2021 can clearly be seen, with London and the South East pulling the average rate of price growth for the rest of the country down over this period. These months approximate roughly to the time when the SDLT tax holiday was operational in England, and the LTT tax holiday was applicable in Wales.

It is evident that growth rates were higher outside London and the South East of England where the SDLT holiday had more impact. Looking at April 2021 in particular, i.e. one year ago, we can note that rates excluding London and the South East were at 11.8%, while including these two areas brought the average rate in England and Wales down to 7.9%, some 3.9% lower.

The reason for highlighting these rates is to point out that the north/south divide which can be seen in Figure 2 above largely arises from the differences in the starting points for the comparison around annual rates of change. If the North of England had not been at 13.3% some twelve months earlier, then we would be reporting a far higher change in prices for April 2022. Looking at Figure 3 above, we can see that the differential between the two groupings in terms of annual price growth continued through to July 2021, so we can expect to be describing a heightened north/south divide for at least another two months.

Property Types

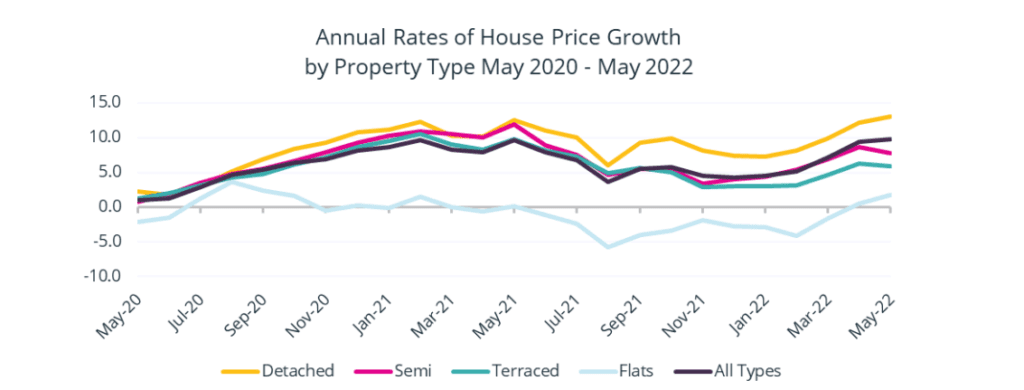

Figure 4. The annual change in house price growth in England and Wales, for the two-year period from May 2020 to May 2022, by Property Type.

Figure 4 above shows the different movement in average house prices in England and Wales over the period from May 2020 to May 2022, analysed by property type.

As can be seen detached properties had the highest rates of growth over this period, with semidetached and terraced properties both having lower rates, broadly similar to each other. Also clear are the far lower rates of price growth – frequently negative – associated with flats over this same period.

The high rates of price growth seen for detached properties is perhaps not too surprising. As has been well documented, the pandemic resulted in life-style changes relating to the purchase of homes, with many buyers seeking out larger properties to enable them to “work from home” – which became known as the “Race for Space”. Additionally, other buyers sought out second homes in areas of natural beauty and coastal locations to enable them to take “staycations”, as foreign travel became largely prohibited. The accompanying competition for these larger properties resulted in increasing prices.

Flats over this period were subject to two separate factors. Firstly, there was the corollary of the “Race for Space”, in that flats rarely have their own private gardens or an extra room which can be converted into an office area. Consequently, there was a general tendency for those looking to purchase a property to move up the housing chain in terms of usable floor area, which reduced the demand for flatted homes. At the same time, following the cladding crisis associated with the aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire, lenders required an EWS1 certificate to ensure that the flat was “fit for purpose”. In many cases these certificates proved hard to obtain, which similarly reduced demand for flatted properties. Hence the price of flats failed to keep pace with other property types.

There is some evidence from Figure 4 that the price of flats is once again beginning to climb. In part, this is due to the return of workers into the larger conurbations, as the requirement to “work from home” is no longer part of Government policy. Additionally, there is a pick-up in demand from foreign nationals for centrally-located premises, as well as the fact that not all flats required remediation and were increasingly good value relative to the stock as a whole. As reported earlier, this has led to large upswings in price in areas such as the City of Westminster, where flats represent some 90% of all properties sold.

Monthly Price Trends

In our latest Unitary Authority report on the April 2022 market, which takes into account March, April and May sales, prices have increased by 0.8%, compared to the previous month (the report is available on the Acadata website – see Unitary Authority Analysis). Of the 110 areas in England and Wales, 77 saw prices increase in the month, with falls in 33 areas. This compares to 73 areas with price rises in March 2022.

The area with the highest increase in price growth in the month was Blaenau Gwent at 6.1%. However, Blaenau Gwent has one of the lowest number of transactions per month of any authority in England and Wales, with only 23 transactions reported in April, which tends to result in volatile movements in average prices, particularly when expressed in percentage terms.

Putting aside the result for Blaenau Gwent, the second highest increase in average house prices in the month was in Milton Keynes, where prices increased by 4.9%. It was the average price of detached homes that increased the most in Milton Keynes, up from £566k in March 2022 to £586k one month later. Detached homes are the most transacted property type in the Milton Keynes Unitary Authority area, representing 31% of all property sales over the last year, against a national average of 26%.

Transactions

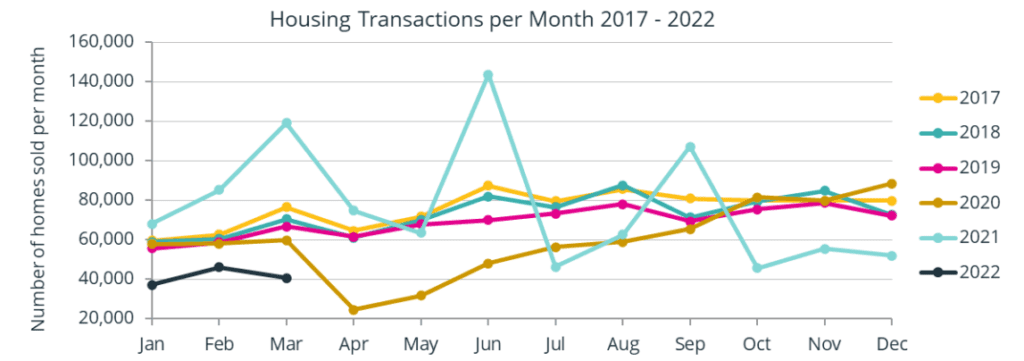

Figure 5. The number of housing transactions per month, January 2017 – March 2022

Figure 5 shows the number of domestic housing transactions per month recorded in England and Wales at the Land Registry for the period from January 2017 to March 2022.

As the chart shows, the years 2017 – 2019 were relatively standard, with not too many fluctuations from one year to the next. However, from the start of the pandemic in March 2020, more pronounced changes can be seen in home-buying behaviour, as housing transactions in April 2020 plummeted, to be followed by a return in housing sales as confidence began to re-build. This then turned into a period when sales exceeded previous levels, as “lifestyle” changes resulted in an increase in demand for homes, especially those with space to allow for “Working from Home”.

There are three conspicuous peaks in 2021 (the light blue line) shown on the graph, along with three associated troughs. The peaks are all stamp duty-related events, occurring in March, June and September 2021. The March 2021 event was one month before the original date planned for Chancellor Sunak’s SDLT tax holiday to end – this termination date was extended to 30 June 2021 at its full rate, and to 30 September 2021 at a reduced rate – but the announcement of its extension wasn’t made until 3 March 2021, and many purchasers already had plans to buy a property within the original timescale – hence the March 2021 spike. The second peak was in June 2021, the final date within which the full SDLT tax holiday was available in England under Sunak’s revised plans, and the final date for the LTT holiday in Wales. The third peak, in September 2021, was the last month of the reduced-rate SDLT tax holiday in England.

Each peak is followed by a trough, indicating the extent to which buyers were able to bring forward their purchases into a tax-saving month, resulting in a lack of buyers the following month when the higher rates of tax were re-applied.

It is difficult to determine whether the apparent lack of sales from October 2021 through to March 2022, compared to previous years, is due to a “true” reduction in sales, or whether this is the result of the Land Registry falling behind in its ability to process the increased number of transactions that took place during June and September 2021.

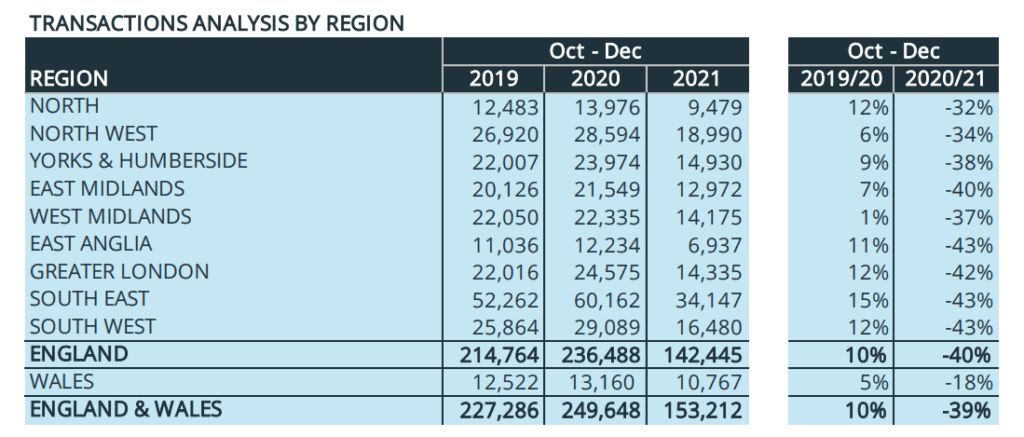

Table 2 below shows a regional analysis of the number of domestic housing transactions that have been registered to date at the Land Registry for Q4 2019, 2020 and 2021. The analysis shows that there was a 10% increase in sales in Q4 2020 compared to Q4 2019. However it also shows a 39% reduction in sales in Q4 2021, compared to Q4 2020.

Table 2. The number of housing transactions per region during Q4 2019, 2020 and 2021

The latest HMRC transactions counts for the same periods are showing a 16% increase in transactions between Q4 2020 and Q4 2019 and a 21% fall between Q4 2021 and Q4 2020. This would suggest that Land Registry has further transactions to record for Q4 2021.

The HMRC provisional estimates for the number of domestic housing transactions in England and Wales in February, March and April 2022 are 85,100, 98,800 and 86,900 respectively, although in the past HMRC transaction estimates are typically 30% higher than the final number of actual recorded domestic sales at the Land Registry.

Help keep news FREE for our readers

Supporting your local community newspaper/online news outlet is crucial now more than ever. If you believe in independent journalism, then consider making a valuable contribution by making a one-time or monthly donation. We operate in rural areas where providing unbiased news can be challenging. Read More About Supporting The West Wales Chronicle