22 January 1879

Written by Philip Thomas (writer & historian)

During a 24-year career with the British Army, I served as the Chief Clerk of 5 Field Squadron Royal Engineers from April 1990 to March 1992. Back in 1879, a young officer from the same squadron would overnight, become a hero of the Anglo-Zulu War and his name was Lieutenant John Rouse Merriott Chard, now famously known simply as Chard VC.

In the wrong place at the wrong time, he commanded the Defence of Rorke’s Drift on 22 January 1879 in what surely was one of the most famous colonial battle of the entire Victorian era.

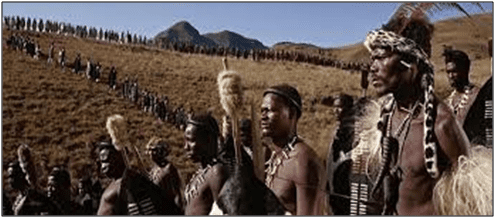

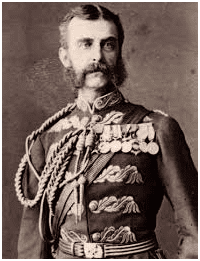

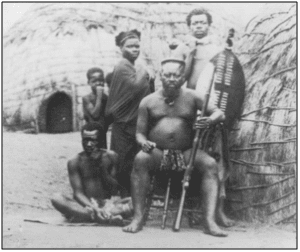

Several hours earlier and just sixteen kilometres to the east, a completely different story had unfolded at the Battle of Islandwana where the British Army suffered its worst humiliation ever by any native force. Around 1,300 British troops under the command of Major General Lord Chelmsford were slaughtered by 22,000 Zulu warriors led by 70-year-old Ntshingwayo KaMahole Khoza, a warrior considered by King Cetshwayo as his greatest general and who had run the ninety kilometres from Ulundi to Islandwana with his soldiers. What Chelmsford did after being replaced for his failure was nothing less than disgraceful as I will explain later but first, let me briefly outline the events that took place at both Islandwana and Rorke’s Drift.

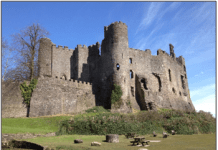

On 22 January 1879, Lieutenant John Chard RE was overseeing the construction of a bridge across the Buffalo River near the small mission station named Rorke’s Drift which the Zulus called KwaJimu,or ‘Jim’s Land’. At that time, a contingent of around one 150 officers and soldiers from B Company, 2nd Battalion 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot were garrisoned at the station under the command of Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead. At around midday, Lieutenant Gert Ardendorff of the 1st/3rd Natal Native Contingent rode into Rorke’s Drift after having fought against the 22,000 Zulus at Islandwana.Three years later, Ntshingwayo would be hunted down by British troops at oNdini and killed after trying to flee and being speared.

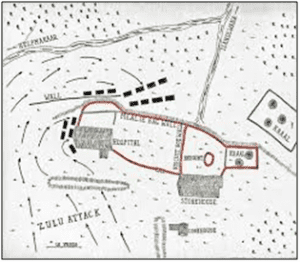

Ardendorff informed Chard that an army of around 3,500 Zulu warriors led by King Cetshwayo’s half-brother Dabulamanzi kaMpande, were heading for Rorke’s Drift to attack the station and that they would arrive at any time. With no time to lose, it was agreed that Chard was the senior officer because of his commissioning date despite the fact that it was Bromhead who was the officer commanding of the troops at Rorke’s Drift. With Assistant Commissary Dalton in attendance, Chard decreed it would be folly to try and outrun the Zulu army and so it was decided that the only option was to stand firm and defend the station.

Work immediately began on constructing a wall built from ‘mealie’ (maize) which would loop from the hospital to the kraal and then, back to the hospital via the store building. A dividing wall was constructed from biscuit boxes which ran from the open north wall to the corner of the store and within four hours, an all-round defence had been established. Soldiers were positioned along the wall and inside both the hospital and store and then issued with ammunition. Rorke’s Drift was ready for the advancing Zulu army.

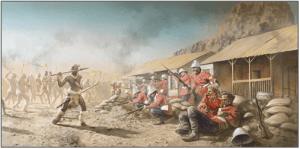

At around 16.00, Swedish missionary Otto Witt and Surgeon Reynolds reported back to Chard that the Zulus had crossed the Buffalo River and were now just minutes away. Otto Witt was allowed to return to his family,but Chard’s numbers were depleted significantly when over 150 local natives employed on General Duties fled in panic. At approximately 16.30, the Zulus reached Rorke’s Drift and formed themselves into the famous ‘Buffalo Horns’ attack formation then around 16.50, the twelve-hour defence of Rorke’s Drift began when Chard’s men opened fire on 600 Zulus who advanced to within 500 yards of the station. Those who survived the hail of gunfire from the Martini-Henry rifles fought hand to hand as spears and bayonets clashed. Time and time again the Zulus would withdraw, reform and attack in increasing numbers from all sides in their effort to wear down Chard’s men.

Ferocious and bloody skirmishes continued for the remainder of the day and throughout the night and acts of individual heroism would soon astound the British Empire, once reports were dispatched that 8 officers and 131 soldiers had fought a large Zulu army in the defence of Rorke’s Drift. The hospital was burned to the ground as wounded soldiers fought for their lives yet throughout all the fighting, only 17 were killed and every surviving soldier was wounded in one form or another. As for the Zulus over 400 lay dead. The next morning, the Zulus retired from the battlefield and in full recognition of the bravery and courage shown by Chard’s men, eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded, the most in any one day.

Although heroes in every true sense of the word, some of the recipients unfortunately came to a sad end, as shown in the Roll of Victoria Crosses but the saddest surely has to be,Corporal Christian Ferdinand Schiess VC. History will forever show that on 22 January 1879, the British Army suffered its most humiliating defeat at Islandwana and its greatest victory at Rorke’s Drift. So, what went wrong at Islandwana?

In short, the Battle of Islandwana was lost through poor command by an over ambitious and egotistical Lord Chelmsford who made huge errors of judgement such underestimating the will and the might of the Zulu warrior. To give other examples, Chelmsford deployed two thirds of his troops in pursuit of what he incorrectly believed was the bulk of the Zulu army and in doing so, compromised his defences beyond comprehension. Another was Chelmsford’s lack of scouting and reconnaissance patrols which for any military commander, is a basic yet essential method of understanding the local terrain and in this case, was where large numbers of Zulus were massing in readiness to attack the British. At around 11.00, a scouting party finally discovered the Zulus who immediately began their attack and after one hour, Chelmsford’s men were literally fighting for their lives.

Colonel Harness who was at Mangeni Fall, on hearing of the events at Islandwana deployed a number of his troops to return and support Chelmsford but were told to turn back after one mile, by an order sent by Chelmsford himself. This proved the fatal mistake and as a result of his errors, Chelmsford was held in great displeasure by Prime Minister Gladstone on his return to Britain.

From a personal point of view and as a former soldier, I believe war is not always a ‘just cause’ to resolve a dispute either between counties or nations however, what I do consider most unacceptable is the person who tries to evade responsibility for their failings by placing blame on others. It is both dishonourable and dishonest, yet this is exactly what Lord Chelmsford did, much to the annoyance of politicians and public alike when the truth came out.

Let me give you just three examples of the lengths to which Chelmsford went in his attempt to elude blame:

Let me give you just three examples of the lengths to which Chelmsford went in his attempt to elude blame:

- He prevented survivors who fought at Islandwana from telling what actually happened during the battle.

- He blamed lack of ammunition for his defeat.

- To his shame,he blamed the deceased Lieutenant Colonel Dunford Royal Engineers of violating an order to defend the position. What Dunford actually did was to take his men and try to fend off the attacking left ‘Horn’ of the Zulu army to try and protect Chelmsford’s flank. He died in doing so.

For me, the sad legacy of 22 January 1879 is this. Many of those awarded the Victoria Cross at Rorke’s Drift and Islandwana faded into insignificance over time yet Chelmsford’s dishonest account to Queen Victoria, led to his promotion to General. I will leave that thought with you.

Help keep news FREE for our readers

Supporting your local community newspaper/online news outlet is crucial now more than ever. If you believe in independent journalism, then consider making a valuable contribution by making a one-time or monthly donation. We operate in rural areas where providing unbiased news can be challenging. Read More About Supporting The West Wales Chronicle