(1 x 60 minutes Testimony Films documentary for BBC Wales)

(1 x 60 minutes Testimony Films documentary for BBC Wales)

Broadcast date: Tuesday 9 November at 9pm onBBC One Walesor on demand via the BBC iPlayer

Repeat Broadcast date: Thursday 11 November at 11:15 pm on BBC Two Walesor on demand via the BBC iPlayer

VERY SHORT VERSION

Four inspirational people, deeply affected by personal experience of the conflict in Afghanistan, tell their extraordinary stories in this inspiring film.

SHORT VERSION

Four inspirational people deeply affected by the conflict in Afghanistan – two soldiers who overcame PTSD, one who lost a leg, and a bereaved, campaigning, mother – tell their extraordinary stories of anguish, despair and recovery, reveal how they coped with the consequences and have strived to help others. This is their story of Surviving Helmand.

LONG VERSION

Four people deeply affected by the conflict in Afghanistan tell their extraordinary stories of anguish, despair and recovery, reveal how they coped with the consequences and have strived to help others.This inspiring documentary on Helmand combines dramatic archive footage with the emotional testimonies of three Welsh soldiers and a bereaved mother. It explores the traumatic experiences of witnessing injury, death, disability and bereavement,yet what shines through is their courage and determination to survive and help others.

At the height of the war in 2009 and 2010 the biggest threat to the soldiers were Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) –increasingly sophisticated and devastating home-made bombs planted by the Taliban. Activated by pressure from above or a command wire, they became the single largest cause of fatalities and injuries. With increasing exposure to these devastating and indiscriminate devices they also became an effective psychological terror weapon.

Geraint (‘Gez’) Jones from Wrexham joined the Royal Welsh Regiment looking for adventure. But his experiences in Helmand were very different from his expectations of being a soldier at war: “The IEDs were hard to detect. You’re not a bomb disposal expert, you’re an infantry soldier. We knew it could be any of us. You could be looking down and both your legs are stumps and you’re bleeding to death. The reason I find that upsetting is because I’ve seen it and what that does to families. When the war was over I felt like a failure, I started drinking. Then I started using drugs every day because I didn’t want to face reality.”

Geraint recovered after he left the army, focussing on physical exercise andhis love of the outdoors, wrote a best-selling book, Brothers in Arms, based on his experiences, and has forged a successful career as a podcaster and writer of historical fiction. “The moment we say, ‘I’m a soldier. I’m broken. The war did this to me’. The more you’re a victim you give up all your agency. The more you do that you’re out of the fight…life is a battle”. “When you’re in that black hole of depression, of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, it doesn’t feel like there’s a way out. But there is. And there’s more than one way. There’s loads of ways out of it”. “PTSD has helped me. It gave me my rock bottom…Now I can see war was a chapter in my life. It’s not the whole thing. It doesn’t have to define me. Is it going to leave a mark on me? Absolutely. But I get to choose if that mark is a good mark or a bad mark”.

Steve Owen from Cardigan was another who signed up looking for adventure. But in 2010 Steve’s Jackal reconnaissance vehicle hit an IED: “It threw us into the air. I ended up on my back with my legs sticking up out of the hole the IED had just caused. I was losing a lot of blood. It suddenly dawned on me that I could potentially die. I could just feel my body shutting down. In the back of my body armour I had a photo of my wife and my son and I remember looking at my mate and I said, “If you do anything for me, get me that photo.” I think that really gave me the energy to keep fighting through and not close my eyes. Because I guarantee if I had closed my eyes, I don’t know if I’d have woken up.”

Steve’s injuries were severe, but it appeared that his injured right leg would be saved. However,he was eventually medically discharged from the army and after fifteen operations Steve was still in such terrible pain that he decided to have it amputated. This would be the beginning of a new life for Steve and his family: “I haven’t looked back since. It was a massive relief that the pain had gone and I could walk well with my prosthetic leg.” Just four months after his amputation Steve completed a 26-mile sponsored walk. Now with three children and a happy marriage he is embarking on an even more ambitious long-distance continuous walk to raise funds for Woody’s Lodge, a charity that supports veterans of the armed forced and members of the emergency services, and where he works as a project manager: “I won’t let my disability define me”. “It’s about giving something back to the guys that we lost. About saying it wasn’t for nothing”.

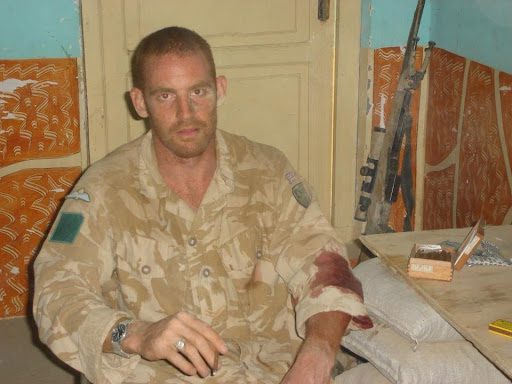

Hugh Keir from Crynant in the Dulais Valley near Neathwas a sniper in the 3rd Battalion TheParachute Regiment (3 PARA): “Helmand was my first experience of a fire fight.It lasted about ten minutes. It was absolutely crazy. I wasn’t used to it.” He was trapped in the siege of Musa Qala and was at the mercy of daily Taliban bombardments and assaults. The continual expectation of a mortar round hitting his shelter took its toll: “It shook me, it was the first time I ever felt fear. It was helplessness”. Being a Sergeant meant he put his role and responsibilities to others before himself: “You can’t afford to think about it”. Like many veterans it took years for Hugh to get help for his PTSD: “I was drinking and contemplated taking my own life twice. I confided in my dad, and he said, “Look what it would do to your mother?” I didn’t want to hurt her or my kids so that pulled me back.” As part of his recovery Hugh started a podcast – ‘H-Hour’- and a rugby team, the Forces Barbarians RFC – or FUBARS – to help others suffering from PTSD. “It became really important for me to try and help people understand what it’s like at the bottom, but also to understand the obligation isn’t necessarily on the ill person– the person feeling crap or suicidal – to reach out for help. The obligation is equally on people, communities, society around to provide an environment where they can reach out…”.

Most challenging of all for families back home was the loss of a loved one. Sarah Adams from Cwmbran was proud when her young son James Prosser said he was going to join the army: “When I saw him on parade in his uniform he looked amazing – like a man, not a boy.” James drove a Warrior Infantry Fighting Vehicle at the height of the IED attacks and in September 2009 the news that Sarah feared most arrived one morning. There was the dreaded knock at the door, and uniformed men on her doorstep there to tell her James was dead. It wasn’t until later that she found out the details of what happened: “An IED blew the Warrior James was driving up into the air. He was semi-conscious when they pulled him out. They got him into a helicopter and took him to Camp Bastion, but they were unable to save him. He died from head injuries and an aortic [major blood vessel] tear”.

James received a full military funeral in Cwmbran which provided some consolation for Sarah. But the trauma wouldn’t go away. With the war still raging, she felt she had to go to Camp Bastion where James had died to try and find some resolution to her grief. She went to Downing Street to lobby Prime Minister Gordon Brown, but although he was sympathetic, he felt it was too dangerous. This strong and tenacious woman then launched a one-woman campaign to persuade the Ministry of Defence to let her go – and she succeeded. Sarah flew to Camp Bastion in June 2012, three years after her son’s death: “I wanted to be where he closed his eyes for the last time. It was so overwhelmingly important to me”. Upon her return to the U.K., hshe campaigned to improve service conditions for the soldiers and advised the army on how they could take a more sensitive approach to bereaved families. This NHS worker continues to be an ambassador for ABF The Soldiers’ Charity, and in 2021 she was awarded an MBE for her services to the Armed Forces and their families.

In this film, four inspirational people discuss the trauma of service, injury or bereavement in Afghanistan and reveal how they have used their courage and resilience to benefit others. This is their story of Surviving Helmand.

| [donate]

| Help keep news FREE for our readersSupporting your local community newspaper/online news outlet is crucial now more than ever. If you believe in independent journalism,then consider making a valuable contribution by making a one-time or monthly donation. We operate in rural areas where providing unbiased news can be challenging. |